On strong flavors, fake burgers and the potential of pea stew

Prof. Dr. Thomas Vilgis is a physicist, enthusiastic cook and eater. He has combined his passions for many years in his position as group leader at the Max Planck Institute for Polymer Research in Mainz, where he studies foods and their properties in the laboratory.

Felix Bröcker in dialogue with Prof. Dr. Thomas Vilgis

Unlike many gourmets, who excitedly and passionately discuss preparations, recipes and restaurant visits, Thomas Vilgis pursues his passion very soberly. He does not follow any ideology, but trusts his experience and scientific knowledge. According to the motto: “On a molecular scale, there is no such thing as politics – everything else is opinion, belief, or view.”

Thomas Vilgis also lets others benefit from his knowledge. With articles in Journal Culinaire, of which he is co-editor, in Effilee, or Essen und Trinken, and in books such as Aroma – Die Kunst des Würzens, Kochen für Angeber, Der Gastronaut, or most recently Biophysics of Nutrition, he also brings his insights into domestic kitchens.

He talked to us about the pros and cons of substitutes and explained the potential of glutamate. He never speaks only as a physicist, but always as an enlightened eater.

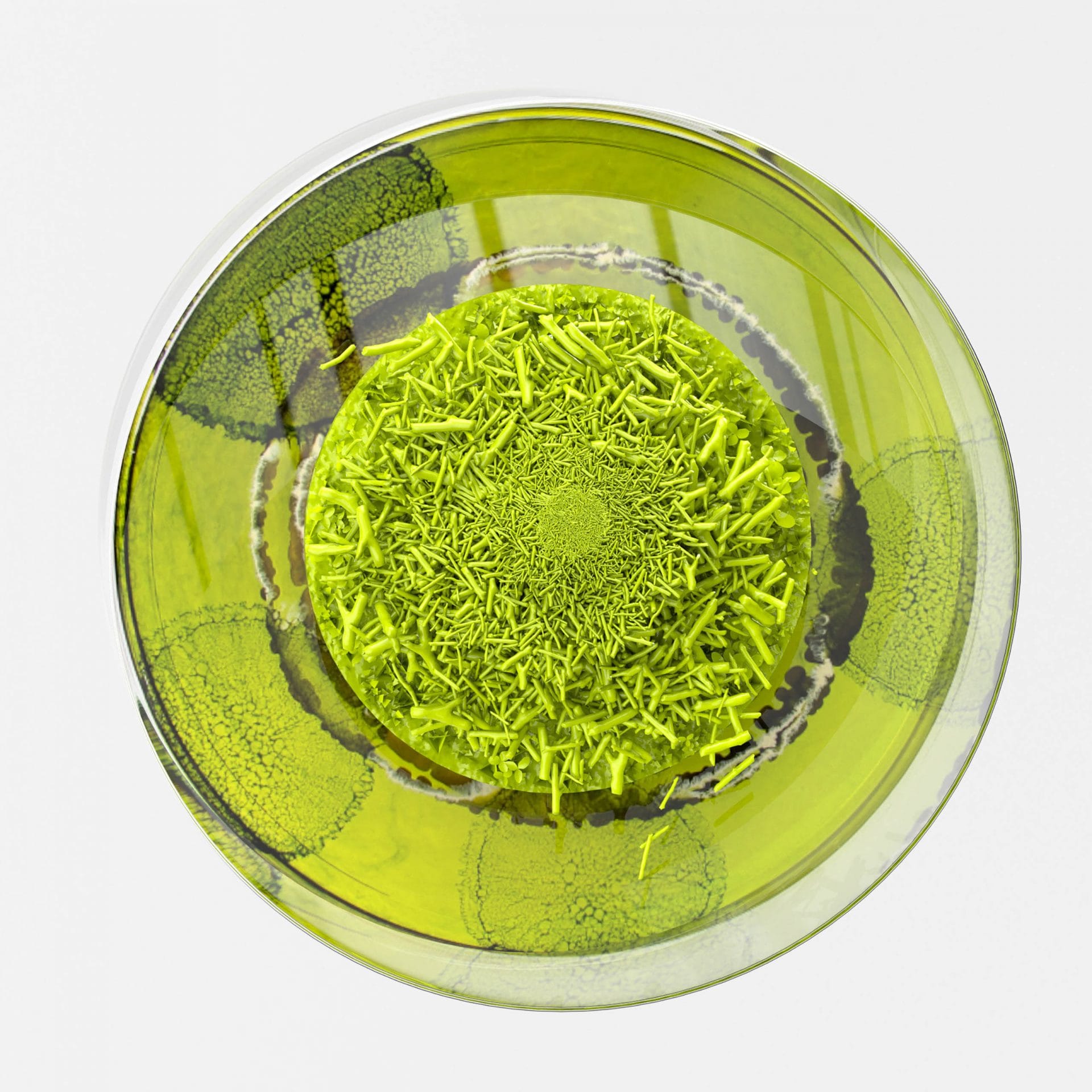

Glutamate: On the nature of the artificial

We are addicted to glutamate. So at Milk, we’ve tried to bring it out in various recipes to provide vegetables with as much umami flavor as possible.

Strictly speaking, glutamate does not enhance the taste of individual foods, so it is not a flavor enhancer in the literal sense, but provides umami flavor and is thus one of the basic tastes along with sweet, sour, salty and bitter (fatty is also discussed). Umami comes from the Japanese and stands for savory. What is meant is a taste image that we associate primarily with hearty, often meat dishes. However, free glutamic acid is also very abundant in tomatoes, ripened cheese or mushrooms, and the content of glutamic acid is particularly high in breast milk.

We have developed various purely vegetable products such as jerkies, apple Maggi, dulse stock cubes and a mushroom burger patty.

A taste advantage through technology

For this we used cooking techniques such as roasting, grilling, fermenting or reducing, and ingredients that are high in glutamic acid (seaweed, mushrooms, celery). We did not want to add pure glutamate. It’s like doping in the kitchen and it feels wrong. But what really speaks against it? Finally, natural vs. artificial is a misleading distinction. This is because pure, isolated glutamic acid cannot be divided into natural and artificial at the molecular level.

As always, it depends. Thomas Vilgis, at any rate, appreciates artisanal techniques for flavor optimization but is also not afraid of pure glutamate.

No fear of MSG

“Glutamate is like refined salt – I have both in the kitchen”. Too much can destroy the flavor balance of a dish, but it would be quite bland without it. And neither glutamate nor salt is dangerous per se – here, too, the dose makes the poison. He likes to use it for desserts. A little glutamate on strawberries, for example, provides an interesting contrast and combines fruity sweetness with umami.

It is important to understand that glutamate is not a flavor panacea. Similar to how vanillin may taste like vanilla, this isolated flavor lacks the complexity of vanilla. Artisanal cooking processes not only increase the content of glutamate, but also provide a concentration of flavors or change the taste through other processes that occur during cooking. A lot of glutamate therefore does not always help much, but makes dishes taste unilaterally like umami.

It becomes clear that Thomas Vilgis is not concerned with ideologies in the kitchen, but with approaching things with reason and deciding accordingly what, when and how to use – or as he says himself: “First switch on the brain, then the stove”.

Substitute products: “Fakeals” or proteins that save the world

Thomas Vilgis provocatively speaks of “fakery” when it comes to substitute products. We have already made a few substitutes ourselves and were mostly quite taken with them. Like our Cashcow cheese made from cashew kernels. So what exactly is the problem here?

Surprisingly, Thomas Vilgis does not initially argue from a scientific point of view, but rather from a cultural perspective. A cheese made from cashew kernels has a completely different cultural background, which has nothing to do with that of a Camembert. To suggest that is wrong, he said. “Fake News,” so to speak.

A new food culture?

At the manufacturing level, some substitutes dig quite deep into the bag of tricks of industrial food production, he explains further. This is because different peptides and amino acids create a different taste pattern in such analog products, which then has to be corrected.

This is even more extreme with some burger patties without meat. These are highly complex and highly processed foods. If a patty is produced from a high-quality pea at great expense, with many components of the pea being sorted out, the result is a “fakealie,” according to Thomas Vilgis. Moreover, this no longer has anything to do with traditional craftsmanship, and he sees this as a danger of further alienating people from their food. But might these products still be a way to make human greed for meat sustainable? To protect the food culture, Thomas Vilgis does without such products. In terms of taste and nutritional physiology, he prefers a pea stew, which can also be vegan.

Solutions and new problems

But if such products have a positive impact on the treatment of animals and the environment, they could certainly be put to good use. For example, wherever meat is used en masse, but its quality is secondary to the taste experience.

“It is precisely at these points that fakery is golden. Because animals are far too valuable for this and die unjustly. Fakealien are therefore a perfectly justified step to counteract the abhorrent factory farming”.

Nevertheless, Thomas Vilgis sees a parallel to the current meat industry: From the pea, components are isolated that are sought after for a certain premium product – exactly the opposite of the nose-to-tail philosophy that currently encourages many meat eaters to enjoy not only the tenderloin.

“A pea is just much more than its “high quality protein”, the “loin” so to speak. Much of what is done there can only happen because we ultimately view vegetables as less valuable and with less emotion than wide-eyed animals.”

And what about other high-quality protein sources like insects?

“Then 2000 animals are killed for a burger instead of using 1/2000 of a dead animal”

This may sound exaggerated and like a relativization of a meat lover, but such a perspective is nevertheless thought-provoking. Ultimately, these are questions of bioethics and are no longer in the physicist’s area of expertise; eating is an interdisciplinary matter. What is clear, however, is that solutions for the nutrition of the future raise new questions that are not so easy to answer.

With heart and brain for the pea

That’s exactly why Thomas Vilgis sticks to the classic pea stew or meat – but not necessarily a filet, and certainly not every day. He appreciates offal such as liver, kidneys, heart, brain or testicles as well.

This makes many people shy away, but why actually? Becoming a knowledgeable eater, capable of appreciating a wide variety of foods for what they are, is not only a matter of taste, but also of culinary education. Sounds exhausting and time-consuming – but is perhaps less complex than the production of some substitute products.

Fake is not equal to fake

In addition to highly processed substitute products that don’t appeal to everyone, there are products that are lovingly produced with high-quality craftsmanship, such as our Cashcow cheese. This is more in line with the culinary demands of a gourmet, but it is still not Camembert. Marketing as an analog product may help some customers to better appreciate something new as a known product. Finally, people are neophobic and avoid potentially dangerous new foods for safety.

Thomas Vilgis has no such fears, he enjoys, for example, vegan cheese made from nuts or seeds as a product with mushroom flavors, gladly accompanied by a good red wine and baguette – But as what it is: “a super exciting nut product” – everything else is cheese.

What we like to eat and why can have very different reasons. Pleasure? Saving the world? Conviction or simply hunger? In any case, we have the opportunity to choose from a very wide range. In order to be able to decide at all, an examination of our nutrition is necessary and helps to make a self-determined choice.

Personal details: Prof. Dr. rer. nat. Thomas A. Vilgis studied physics and mathematics in Ulm, followed by research stays in Cambridge, London and Strasbourg. He is a research group leader at the Max Planck Institute for Polymer Research in Mainz for soft matter theory (from a physicist’s point of view, food is nothing else), statistical physics of proteins, molecular biophysics, and physics and chemistry of food, among others. He is co-editor of Journal Culinaire and author of numerous books on applied science in the kitchen.